Bank of America Neighborhood Builder Grant Award Ceremony

KEYNOTE ADDRESS

Wednesday, November 13, 2019

Chrysler Museum of Art

Norfolk, VA

Dr. Johnny Finn,

Associate Professor

Christopher Newport University

On Wednesday, November 13, 2019, LT/LA Project Director Dr. Johnny Finn was invited to give the keynote address at the Bank of America Neighborhood Builder Grant Award Ceremony. This event was to honor the Lackey Clinic of Yorktown and the Judeo-Christian Outreach Center of Virginia Beach, who each received a $200,000 grant to continue their non-profit work in the region.

THE SLIDES

(click to view full-screen)

THE ADDRESS

Good evening everyone, and welcome to this exciting and celebratory event honoring two important local organizations. First and foremost, congratulations to the Judeo-Christian Outreach Center of Virginia Beach and the Lackey Clinic of Yorktown on each being awarded a Bank of America Neighborhood Builder Grant. The work that these two organizations do is so important to our community and indeed to the entire region. The recognition bestowed in this award is well deserved, and the generous funding and leadership development training that comes along with it will be transformational for these organizations, and more importantly, for the entire Hampton Roads region.

It’s worth reflecting for a moment on the scale of the impact that each of these organizations has. The Lackey Free Clinic of Yorktown offers a truly impressive menu of primary, chronic, and specialty medical care; dental care; and pharmaceutical coverage to over 1,600 uninsured, low-income patients from across the Peninsula. That number will double with this new funding. Every single day, the physicians, nurses, and staff of the Lackey Free Clinic are on the front lines of a health care crisis in this country.

For its part, the Judeo Christian Outreach Center of Virginia Beach operates a host of feeding and housing programs, including a community dinner every night, Monday through Friday at 6pm, and Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays at 3pm, 365 days a year. Combined with their family food box programs, they serve over 85,000 meals a year. They also run Virginia Beach’s only year-round shelter for single adults, a rapid re-housing program, transitional and permanent housing for homeless veterans, a day support program, and a winter housing shelter. These services could expand to a thousand more individuals as a result of this grant.

Together, these two organizations directly confront some of the most pressing social needs in our community: housing, food, and medical attention.

And these needs across Hampton Roads are great. Thinking specifically of food and food security, food deserts are defined as neighborhoods with relatively high levels of poverty that don’t have any grocery stores or other sources of competitively priced food within walking distance. According to my own analysis, over 200,000 people, or about 13 percent of the region’s population, live in areas defined as food deserts. I’ll return to this analysis shortly. In terms of access to health care, across our region, nearly 150,000 people don’t have health insurance, that’s about 10 percent of all residents. And of course, that population is not evenly distributed. And related to housing specifically, according to the Princeton Eviction Lab—which contains by far the most comprehensive national dataset on evictions in the U.S.— Hampton Roads is home to four of the most evicting cities in the country . Let me put that a different way: Four Hampton Roads cities—Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, and Chesapeake—make the top 10 list for highest eviction rates in the country.

In short, the services that the Judeo-Christian Outreach Center and the Lackey Free Clinic provide each and every day are absolutely vital to the health and well-being of our community. Again, my most heartfelt congratulations to both of these organizations. These awards will be truly transformational.

The commitment of each of these organizations to social justice, and the vitally important work that they do in the community should also inspire us to confront, understand, and ultimately work to dismantle the profoundly unequal systems of power that continually reproduce precisely the social challenges that these two organizations combat every single day.

The production of racial and economic inequality, particularly in Hampton Roads, lies at the heart of my research agenda as an urban geographer. When I speak about my research, whether in my classes at Christopher Newport University, or with audiences in lectures that I give around the region and across the country, I find that folks are consistently surprised at the strong through-lines that connect our past to multiple intersecting dimensions of our contemporary urban reality.

As William Faulkner famously wrote, “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Take, for instance, this 1940 residential security map of Greater Norfolk, which includes the cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth, Hampton, and Newport News. This so-called “redlining” map, along with similar maps of nearly 250 other cities in the United States, were official U.S. government documents used to guide refinancing of home loans during the Great Depression. At the core of this program were teams of raters who spread out through urban landscapes all across the country to assess individual neighborhoods’ worthiness for government-subsidized refinancing. Highly rated neighborhoods could be eligible for favorable refinancing while redlined neighborhoods would be barred from the program. Assessors collected all kinds of data, from income to quality of housing stock to whether or not streets were paved. But one single factor matter more than anything else in determining a neighborhood’s credit-worthiness: race. The map of Greater Norfolk rated a total of 96 neighborhoods, redlining 30 of them. Of the 66 neighborhoods that were notredlined, only one area—Phoebus—was reported to have any African American inhabitants at all. On the flip side, half of the thirty redlined neighborhoods were 100 percent Black, while less than a quarter of them were predominantly white.

In the decades following World War II, the federal government expanded its segregationist housing policies, primarily by luring white families into the suburbs with the promise of home ownership (at a subsidized rate), while constructing high density, segregated Black public housing in urban cores for African American families, who were explicitly prohibited from buying into the budding white suburbs.

Other socio-cultural factors, including racial steering by realtors, block-busting, contract selling, and other predatory lending schemes, and discriminatory lending policies by banks, also helped to produce the segregated American city.

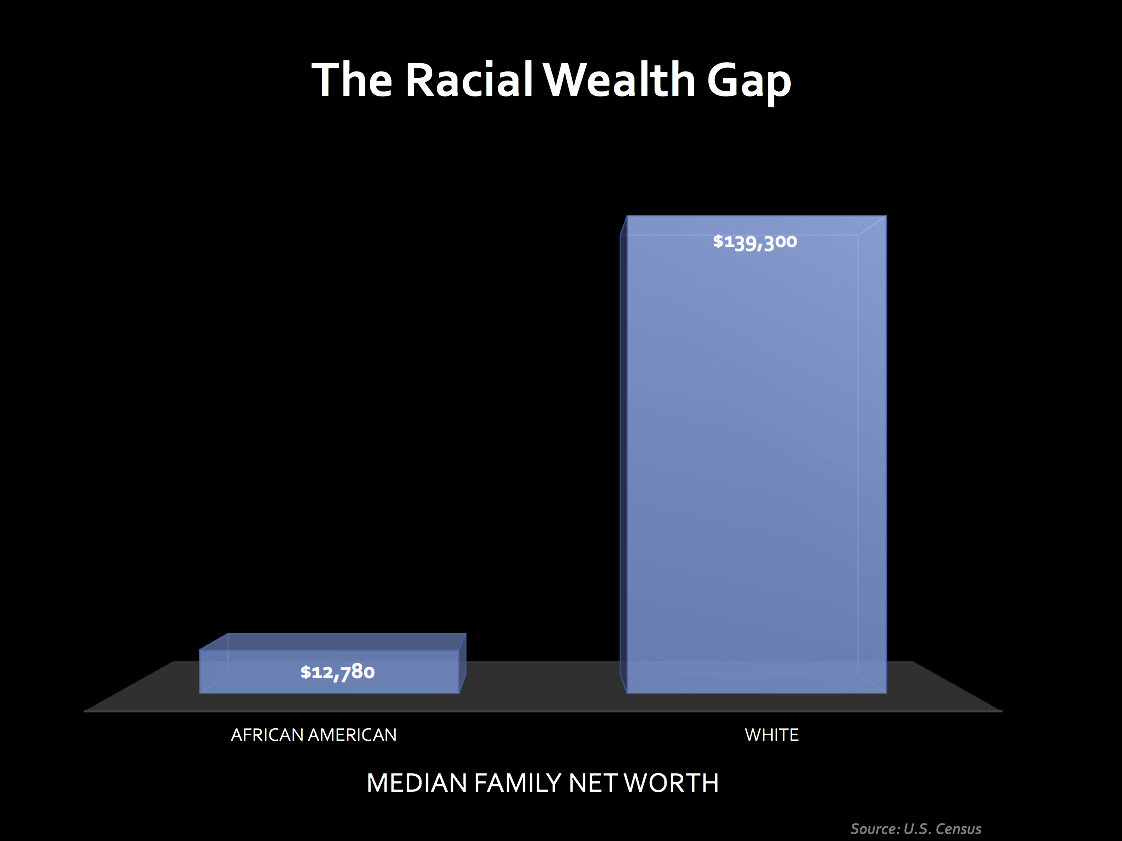

A recent study by the Economic Policy Institute found that these housing policies and practices, which created and protected wealth through housing for white families while explicitly denying the same for Black families, is at the root of what is to me the most shocking statistic I’ll share with you tonight: According to the U.S. Census, in 2015 while the median white household in the U.S. had a net worth of almost $140,000, the net worth of the median Black household was not even $13,000, a racialized wealth gap of over 90%.

The disturbing level of racialized economic inequality in this century is the direct result of decades of racist housing policies and practices in the last century.

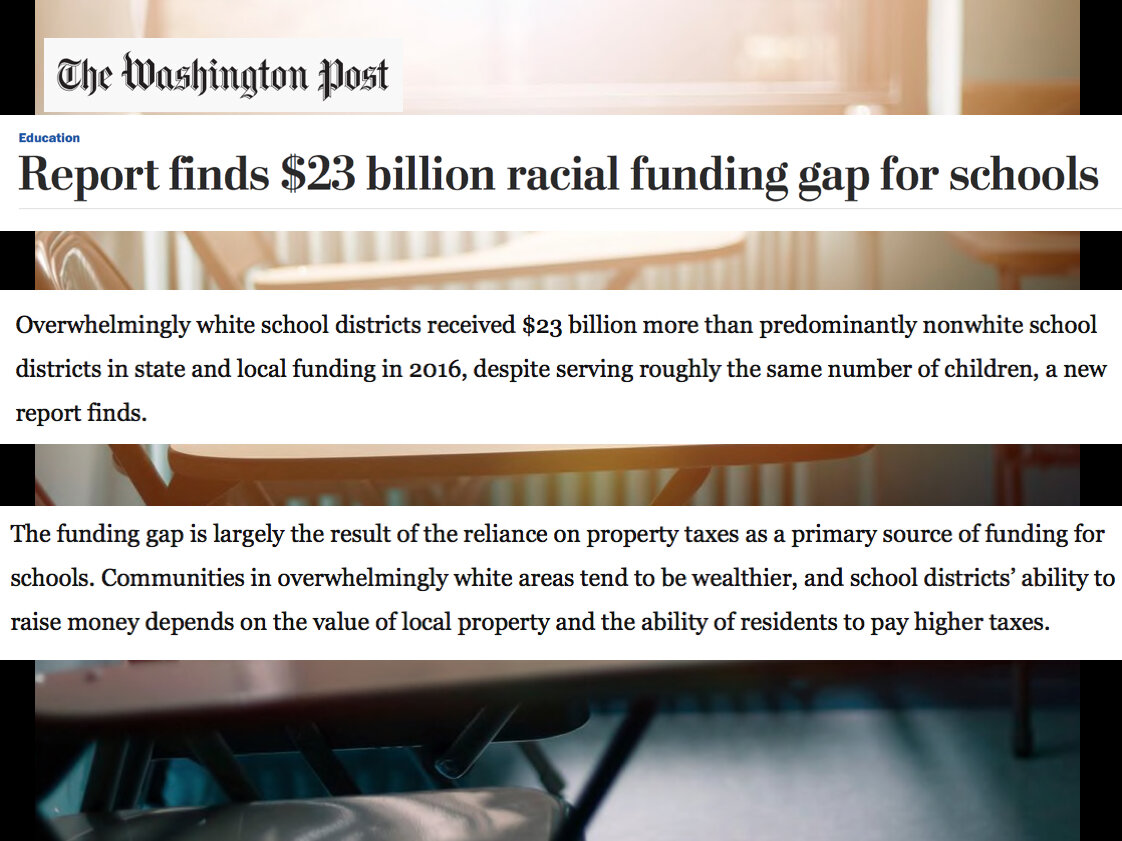

Education, we often repeat, is “the great equalizer of all men, the balance wheel of the social machinery.” But segregated neighborhoods beget segregated schools. And since public school funding in most places in the U.S. is tied to local property values, this racialized wealth gap leads directly to a racialized education gap. The non-profit group EdBuild recently reported that in 2016, “overwhelmingly white school districts received $23 billion more than predominantly nonwhite school districts in state and local funding, despite serving roughly the same number of children.” This report goes on that the “funding gap is largely the result of the reliance on property taxes as a primary source of funding for schools. Communities in overwhelmingly white areas tend to be wealthier, and school districts’ ability to raise money depends on the value of local property and the ability of residents to pay higher taxes.”

The implications of this structural inequality reaches all aspects of life. Thinking back to the food deserts that I mentioned a few minutes ago: while about a third of the total population of this region is African American, nearly 70 percent of people who live in food deserts in the across the region are black. People of color are similarly vastly overrepresented among evicted populations, and lower income people are overrepresented amongst the uninsured.

I hope I haven’t brought down the mood. That certainly wasn’t my intention. Quite the contrary. To me, this overview of the structural foundations of urban social inequality bring into stark relief the vital necessity of the organizations that we’re here to recognize tonight. Without these two organizations, think of the thousands of meals that would be missed by hungry families, hundreds of beds that would go unfilled by veterans and others in need, the doctor appointments that would never be scheduled due to a lack of insurance.

But I hope that I’ve also been able to demonstrate the need to think systemically and intersectionally about the magnitude of the underlying challenges. We have to operate in the world as it is, and we should simultaneously always be working toward reshaping the underlying social foundation to create a more equitable future.

The Lackey Free Clinic of Yorktown and the Judeo Christian Outreach Center of Virginia Beach do both. So congratulations to both on years of achievements. Speaking on behalf of everyone here tonight, we’ll be looking forward to how this award allows each of your organizations to continue to grow, to serve more people, and to make Hampton Roads a healthier and more just home for all. To the folks from the Lackey Clinic and JCOC, thank you for your vital work. And to everyone else, thank you for being here to support these two organizations on this special occasion.